The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of*

The Stuff, the Stuff, the Stuff—What to Do with All of the God Damned Stuff

*Yes I know this is a misquote of Shakespeare but I’m quoting Sam Spade/Humphrey Bogart/John Huston misquoting it in The Maltese Falcon (1941)

Anyone who’s ever had to move, whether they were hiring professionals with trucks and handcarts or just bribing their friends with pizza and beer to carry milk crates across town, has had at least a passing moment like this: What am I doing? Why am I lugging this crap around with me everywhere? Who needs all this shit? When they briefly fantasize about ditching it all, fleeing it, just let the landlord keep the security and throw it all out, while you travel the world, living out of an overnight bag, never even having to check luggage again.

That’s what I’ve been doing for these last five years: subletting or squatting in various locales—some of them swanky, some idyllic, but none of them mine—while my own house was allegedly being rebuilt (long boring story involving incompetent/criminal contractors). My girlfriend of five years has never seen an object I owned, except for my laptop and whatever clothes and books I had along with me. But now, after all that time, the house is nearly complete and I’ve finally retrieved my things from storage, and am at last reunited with my long-lost stuff. My precious, beloved stuff. The stuff, the stuff, the stuff—all of the God damned stuff.

I’m now buying stuff to put my other stuff into: bookcases, a filing cabinet, an LP shelf. It seems I’ll need an entire closet devoted to Obsolete Media: DVDs, CDs, cassette tapes, LPs, photo albums, Super 8 reels, boxes of slides and slide projectors. There are around three hundred dry pens and broken pencils rolling around in a desk drawer, maybe eighty dollars’ worth of assorted change of all nations, and more paper clips than can fit into the magnetized paper clip holder from a decades-defunct copy shop. (In what year did I last use a paper clip?) I’ve also inherited a storage spaceful of my late parents’ stuff—about 250% more furniture than will fit into my house. My father loved going to auctions and estate sales, and would bring home things like a stuffed sea turtle, a copper bowl for candy-making, a carved duck lamp, and not one but two (2) antique post offices. I’ve even inherited the accursed Christmas china. While she was still alive and fully compos mentis, my mother was perversely determined to bequeath me this china—a full set, complete with a soup tureen and gravy boat, each piece decoarated with red ribbons and green holly leaves. I said Oh thanks but you should really give it to someone who’ll love it, but she steadfastly insisted, and I said No, seriously, I never use china at all and honestly I hate Christmas, and she said Too bad—you’re getting it. You can give it away when I’m dead.

So now I have to decide what stuff to keep, what to sell or give away, what to haul to the dumpster or the landfill. I’ve been contacting auction houses, posting things online, giving them away. Do you want any of it?1 A lot of items fall clearly into one or the other category, KEEP or GET RID OF, but then there’s the broad, dispiriting gray zone of things I will never need but also can’t throw out: high school literary magazines, Mom’s student paintings, Dad’s medical school yearbook, beautiful drawings an artist ex-girlfriend did on envelopes. This last category is so vexing that I wrote this entire essay rather than deal with it. Objects that take up drawer or closet space, are of no practical use, but are so charged with association and heavy with guilt that you drag them around with you the rest of your life like Marley’s money boxes. I once dated a woman whose mother, a frustrated artist, had creatively decorated her brown paper school lunchbags every day when she was a girl. She’d saved every one of them.

Don’t get me wrong—it’s very satisfying to put my stuff in order, to lay down carpets and hang pictures and shelve my books, to see my familiar things pleasingly arrayed around me again. But, having been deprived/freed of all this stuff for the last five years, I find myself a little reluctant to take on the burden of it again. A new house is a tabula rasa: I don’t want it cluttered before I’ve even moved in, or to forfeit whole rooms to storage. Over these last years I’d occasionally grouse about not having access to this or that object, or wish I could show my girlfriend a particular photo, but it also occurred to me more than once that if the storage facility where it was all kept were to burn down, I might not actually miss much, except for my childhood teddy bear. Being deprived of my stuff left me untethered—disconnected, adrift, homeless—but untethered also means free.

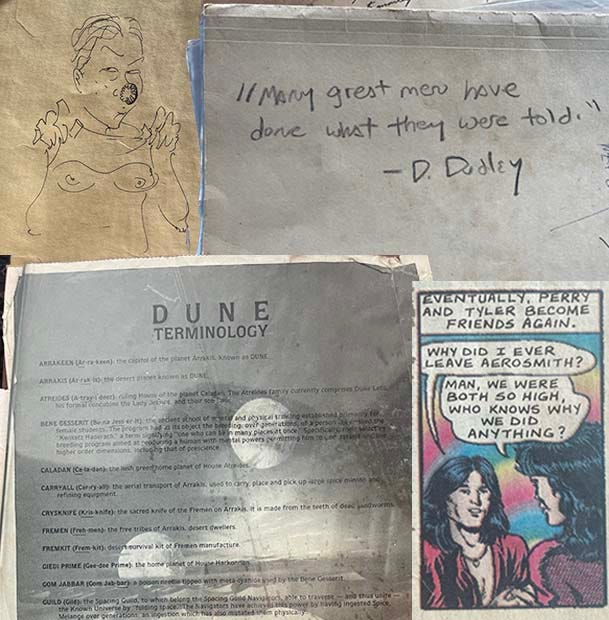

I think what we’re really trying to gain, to hold onto or control, with all this stuff, is time. Stuff is what remains, the solid residue of the evaporated past. So we cling to the stuff in lieu of the lost moments and irrevocable time. People keep obsolete documents and records, taxes and invoices from decades ago, partly as backup, an external heard drive, but this reluctance to part with ephemera must also have to do with a terror of losing your entire life. You keep old party invitations or concert programs or syllabi you’ll never need again because it’s hard to accept that that event happened, but it’s over now, never to come again—to just let it go in the Heraclitean current. I first noticed my mother’s cognitive decline when she got very touchy and protective about the stacks of paper on her desk, telling me not to touch those, she still intended to go through them. When I snuck a look, I realized that 98% of it was worthless—years-old old receipts, credit card offers, articles printed out from the internet. I remembered those premonitory piles while I was transferring all my own papers from the old bunged-up rusted filing cabinet to a new wooden one: bad essays and short stories and memoirs and screenplays, a flyer for the Thrashing Skümz, the 1990 cross-country road trip journal, a comic-book biography of Aerosmith. It occurred to me that, instead of archiving it all chronologically in color-coded folders, I could just put all this shit into a box and haul it down to the beach and set it on fire. Because of course we all lose everything in the end; everyone’s memory is a Library of Alexandria, doomed to annihilating flames and long, barbarous darkness.

But it isn’t as simple as just getting rid of everything: the problem with my mother’s piles was that one in every five hundred papers was an important document. And in my own files I do find the odd treasure, like the glossary of unfamiliar terms that was handed out in theaters showing Lynch’s Dune in 1984 as a desperate audience-comprehension aid. Sometimes you really do regret losing things; where, for example, is my cool Star Trek poster with the cutaway view of the Enterprise? Surely I wouldn’t have gotten rid of that. Decades ago I threw out an ambitious drawing I did in high school, which my pretentious college self thought was pretentious. Now, in middle age, I think of both those people as kids, and of that decision as a crime against my former self.

My own memory has suffered in the last few years, some of which is an effect of the pandemic—that year of isolation and stress acted like an electromagnetic pulse that wiped out all stored electronic information, except from brains, not computers—but I also suspect that some of it has had to do with being separated from my stuff. Stuff provides continuity with the past, serves as a kind of mnemonic. (I’ve always remembered a little tchotchke, a green glass egg with a clear bubble in it, that quietly endures in the background of all four books and decades of Updike’s Rabbit tetralogy.) I have had The Fearsome Nosferatu Mask since middle school, and yet when my girlfriend asked me where it had come from I realized, in a low-grade panic, that I couldn’t remember. But gradually the connections are re-forming. Who painted this “Godzilla vs. Sleestack” picture…?—oh RIIIGHT, Kara, the naughty art student! It’s like excavating the lost civilization of Me, all its ancient texts and artifacts, reassembling the fragments and documents to reconstruct a history. I keep sending photos of old notes and doodles to friends, the original sources of in-jokes that’ve since passed into idiom. I have to tamp down ill-considered impulses to write notes to people who have no need to hear from me ever again just to say Hey, I remember you!, the way people helplessly blurt at celebrities, Hey, you’re [that celebrity’s name]!

But this stuff also keeps me tied to the past, bound to it—to my family, my history, to Past Me. By taking on the burden of my stuff I’m also reassuming a whole cumbersome self—the drunk guy in all these old party photos, who drew these angry, hilarious cartoons, who thought he needed to own all these things—and the baggage of a past that may or may not have much to do with me anymore. All the unwanted Christmas china foisted on me by genes and upbringing and history and chance and decisions I made for reasons I can’t remember. Unaccommodated man is a truer picture of us than our official portraits, robed and enthroned in all our stuff. Having nothing forces (or allows) you to remain fluid, to be whatever you actually are in that moment, instead of everything you’ve been and accumulated over the decades. Even if what you are right now isn’t much of anything, being shorn of your stuff at least lets you recognize that, the way shaving an area lays bare a wound or a site for surgery.

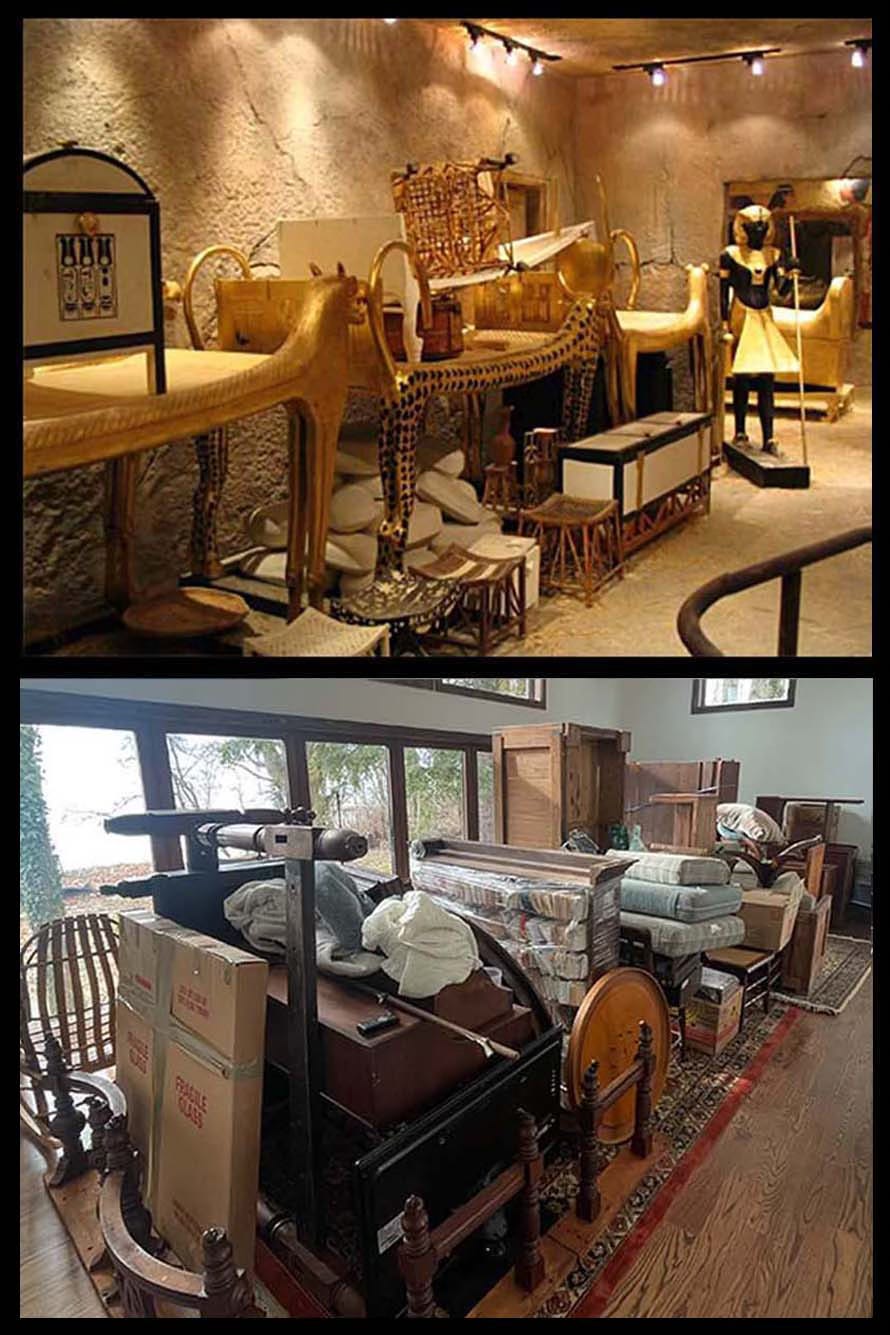

We surround ourselves with stuff not only to advertise an image but to tell ourselves who we are, reassure ourselves of our substance, stability and permanence. It’s an existential hedge against fragility and evanescence. Way at the far end of this continuum from me with my stuffed sea turtle and Fearsome Nosferatu Mask are the pharaohs taking their entombed treasures with them to the afterlife, Sardanapalus having his concubines killed before him on his funeral pyre, or William Randolph Hearst stacking his castle with the plunder of the world. Or, more recently, specimens like Musk or Trump encasing themselves in all the armor of wealth and power to try to turn themselves into colossal invincible mechas, and conceal the stunted, loveless little boys within.

My friend Harold is having none of this bullshit; he scorns any sentimental attachment to the past, I suspect because sentimentality is such a danger to him that he needs to quash the impulse in himself. He once told me about traveling back to the town where he’d gone to grad school, a happy period of his life, only to find it changed beyond recognition. The past is gone, he decided; trying to revisit it can only disappoint you. What matters is the present, because that’s all that exists. Harold’s apartment is spartan as a hotel room or model condo—white walls with a few discerningly chosen pieces of original art framed behind museum-grade glass, and a book collection draped behind towels to protect it from UV damage. Harold intends to come up to my place this spring to “burn his papers” in the flame pit down on the beach.

At the other end of the possession spectrum is hoarding—in its extreme form, a DSM-certified mental disorder,2 but not uncommon as a general tendency, especially as people grow older. Hoarding correlates not only to trauma but the tendency to anthropomorphize, imbuing objects with soul and subjectivity. To some extent this is an innate human trait: animism predates any organized religions; all children personify their dolls and stuffed animals. It’s true I feel more pity for uneaten food than is strictly speaking reasonable, and have been known to reprove my girlfriend not to speak unkindly of certain objects, at least not right in front of those objects. This is obviously silly when we’re talking about mashed potatoes or a thrift-store teapot, but it starts to feel less irrational with regard to my father’s to-do lists, written in his distinctive elongated, flattened hand. I was disproportionately upset to see that a photo of Dad and me in our front lawn taken one Easter Sunday some thirty years ago—he looking like a distinguished physician in his 50s, waving gamely to the camera, me a twentysomething goofball in white pants, suspenders, and a tie I bought while on LSD—had been water damaged. Throwing out that med school yearbook, which I will likely never look through again, still feels like obliterating a last remaining trace of his passage through the world, killing off another piece of him. Because people don’t last, but Stuff does. These items are still imbued with human personality, animate. (Slashing portraits, burning effigies, and toppling statues are only symbolic violence—but the objects of that violence take it seriously.) In Cormac McCarthy’s screenplay Whales and Men a character laments, looking through his ancestral photo album, “that their most enduring reality—and mine—should take the form of a small square of tin or cardboard. Like a form of taxidermy, really.” It was my father who gave me the Fearsome Nosferatu Mask, of course; I remember now. His Dadlike whimsy peers out at me from its bulging undead eyes, as it does from that discolored photo.

It is ultimately absurd: we spend our lives amassing this stuff, hoarding and arranging and cherishing it, but after a generation or two its emotional associations fade like the colors from an old photo, and then when we die our heirs are left with the heap saying, What are we gonna do with all this junk? A better metaphor for our endless pathetic acquisition than grandiose Ramses or Sardanapalus, hubristic Musk or Trump, is Steve Martin at the end of The Jerk: shuffling off in his bathrobe and slippers, clutching his haphazard collection of crap, weepily insisting that he doesn’t need anything—“just the ashtray and this paddle game and the remote control and the lamp and that’s all I need”—pausing, every few steps, to pick up one more random object and add it to the list.

It may be silly and pitiful to attempt to cling to the past and secure some immortality for lost loved ones or yourself, to make a bulwark against entropy and death, with mere objects—tchotchkes and pictures and pieces of paper. But of course that’s what being a writer is—arguably, what most human endeavor amounts to. My friend Harold, the one who disdains nostalgia, is also, I may have mentioned, a rare book collector, devoted to preserving one-of-three-extant-copies of first editions of obscure werewolf novels from 1911 that quite likely no one else will ever read again. Our stuff is all that survives us; our stuff is what endures—fossilized memories, our will trapped in amber. If our species were to go extinct, any interstellar explorers who might happen by a few million years from now will find our geostationary satellites still loyally orbiting on trajectories set by the dead, could discern the fading traceries of our cities from space, like indecipherable doodles. They might even discover the enigmatic faces of some hominids blasted into a mountainside, eroded but still recognizable as the likenesses of hallowed elders or ancestors, still gazing out across the eons like the mask of the Fearsome Nosferatu. In sorting through all the things I’d gotten out of storage, I found among them a box marked: Christmas China for Tim.

Yes, I’m asking you, substack reader: do you want to buy a four-poster bed (I have a double and a twin), an expandable dining room table with twelve inserts/leaves, two end tables with brass claw feet, a circular inlaid-wood table, eight cane chairs, a standing tabletop mirror, or 34 crystal punch glasses? Photos/measurements available on request. Prices negotiable. You’d have to come get them. I guess I could ship the glasses.

Just as a point of interest, check out the International OCD Foundation’s Clutter Image Rating Scale, illustrating progressively pathological tableaus of kitchen, bedroom, and living room (the bathroom is mercifully omitted).

I recall laughingly discussing "Swedish Death Cleansing" with my mom during COVID in an effort to pare down her 'stuff' while she was alive, terrified that I'd have to do it alone once she was gone. All the years of discussing the Christmas Cape Cod china... her worst fears that I wouldn't want to forever lug around 10 place settings came true. In the end I kept only the most important piece: the gravy boat.

Really, this is a masterpiece and so insightful. I've been forced, through divorce and a cross-country move, to shed 90% of my 'stuff.' What you said about 'things' being reminders is so true. I get by without my old things but I still wish I could be around them sometimes, to have that lens through which to see my former self/selves. Thank you, Tim.