Terminal Lucidity

Contemplating Our Converging Crises

I began this essay late last year, in circumstances that’ll become immediately evident, and although I’ve revised it since, I’ve decided it’s essentially an artifact of the moment and the mood in which I wrote it, and to keep trying to update it as history unfolds and my own perspective shifts would turn into a never-ending Red Queen’s race against the present. It seems, in retrospect, too relentlessly bleak—I worry it would disappoint those optimistic angels who float over my shoulders when I write, like Rebecca Solnit and Kim Stanley Robinson. I think there have been hopeful signs recently, from Trump’s popularity beginning to wither in his own party to Kansas’ voting to protect abortion rights to the passage of a climate bill, suggesting that the reactionary backlash of dingbats and bigots may have reached its high water mark. But it’s not as if the metaphorical storm I write about has blown over yet, or will anytime soon.

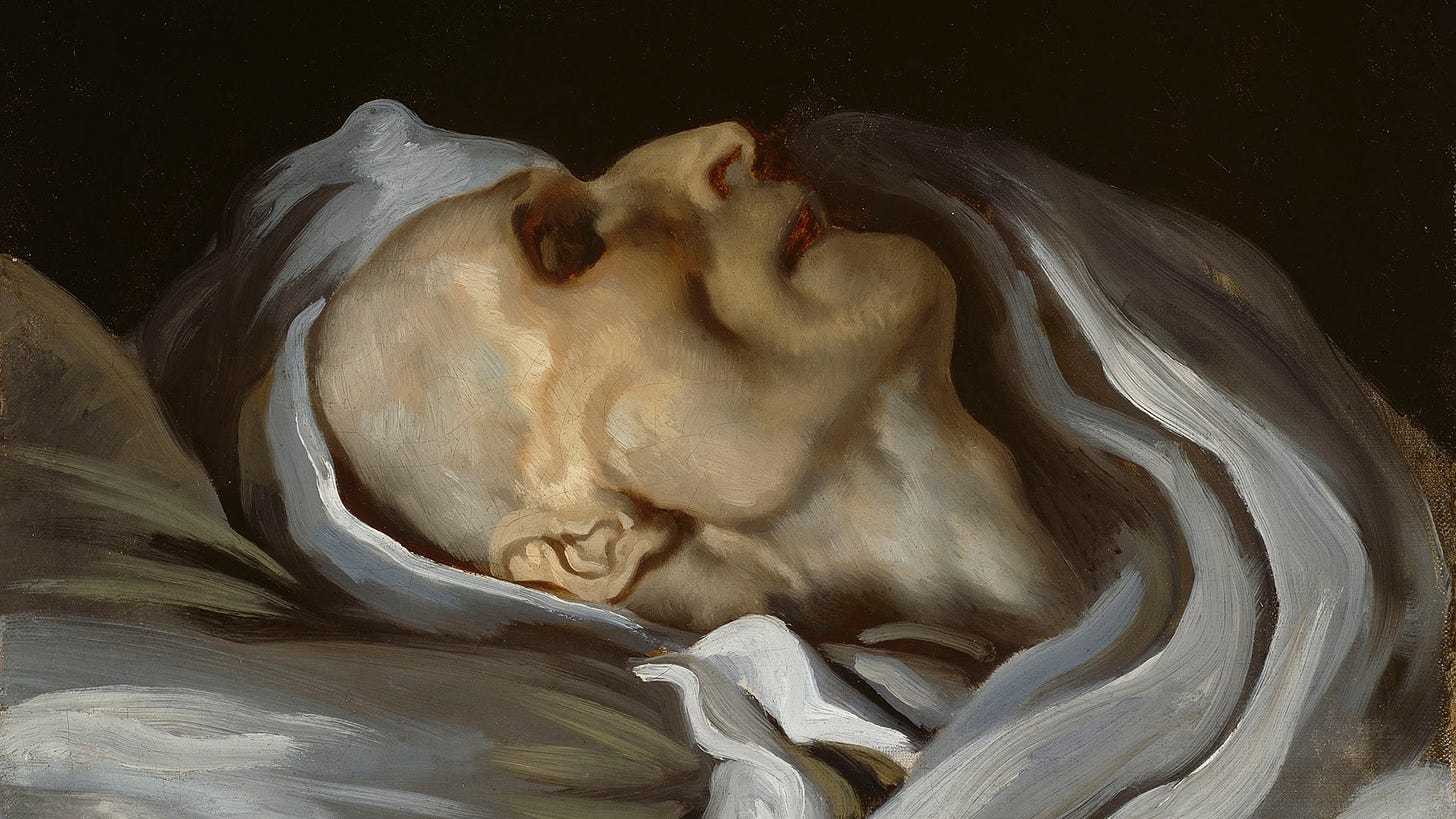

I started writing this essay at my mother’s deathbed. She’d had a degenerative disease for a long time, but, like a lot of elderly people isolated from family in quarantine, she went into a rapid decline. When she stopped eating, my sister and I traveled to be at her bedside, where we spent a strange, uneasy few days—a liminal time, simultaneously stressful and tedious, knowing she wasn’t going to live much longer but unsure whether that might mean days or weeks. “It's a weird place to be,” a friend who’d been through the same thing wrote me, “waiting for something awful to happen, expecting it every day, not wanting it to happen but also wishing it could be over with.”

Does this sound familiar? We’ve all been in a weird uneasy in-between time, ever since Trump was excised from the White House and vaccines became widely available. It’s been something like the eye of a hurricane—a brief false calm when we all let ourselves relax a little, even though we know it’s not over yet, and the worst is yet to come. But who can blame us for having let our guard down, just for a breather? It was such a relief, at first, not to have to wake up and anxiously check to see what new gratuitous crisis, moral atrocity, or affront to common sense and human decency awaited us today—to pretend that things were back to normal, even though we all know that normal is over now, and not coming back. It wasn’t a true recovery but a temporary reprieve—the kind of brief, misleading rally some terminal patients exhibit just before the end. We all feel helpless to avert the converging disasters we can clearly see coming: all we can do is watch in impotent horror, saying “Noooooo” in the slurred bassos of nightmarish slow-motion as the great steaming lump of feces float inexorably fanward.

If you’re not even sure whether I’m talking about the collapse of American democracy or the imminent recession or a third world war or a resurgence of the pandemic or the cascading catastrophes of climate change, it only shows how dire things are on every front. A lot’s happened, what feels like decades of history compressed and accelerated into a few years, like the sort of frenetic, impressionist montage Chuck Braverman used to make, too much to consciously process. Sometimes you have to re-tell it to yourself just to get it all straight and remind yourself it’s all real, the same the way I remember absorbing the reality of a friend’s death in tiny, incremental, concrete steps (“So wait—his physical therapy was all for nothing?” “But what will happen to his cat?”). Let’s try to synopsize:

A virulent pandemic shut down the world for over a year, and though we developed a vaccine against it in record time a lethal percentage of our fellow countrymen just didn’t feel like getting it. A sitting president incited a mob to revolt—and seemed ready to let them assassinate his vice president—to try to retain power after being voted out of office. Russia, led by its dying gangster/assassin dictator, has invaded a neighboring nation with the most contemptuous gesture at pretext in an attempt to revive its old empire. suburban neighborhoods in Germany and Belgium disappeared under the kind of floodwaters associated with monsoons; immense swaths of California and Oregon now catch fire every summer as reliably as the foliage turns in New England; the entire United States, from Seattle to Boston, is suffering triple-digit temperatures normally see only in hellholes like Phoenix. It rained on the ice cap of Greenland for the first time in recorded history, and a chunk of Antarctica the size of Manhattan fell into the sea. I’m probably forgetting something.

Any one of these crises would take fortitude to contemplate; together, they amount to a demoralizing apocalyptic combo: impossible to ignore, impossible to face. None of them is going away, and they’ll all get much worse before they get better. Instead of renouncing the would-be despot and imprisoning him to await trial, his party has adopted his childish lies about a “stolen” election as official policy, disenfranchising as many voters as they can and installing apparatchiks to overturn any future election they don’t win. Even if he doesn’t run again, someone younger and worse will, possibly someone competent, whose ambitions go beyond self-aggrandizement—one of those Republican governors who gladly forfeits lives for poll numbers and sucks up to bullies by picking on kids. Even though the republic survived the initial devastating blast of the Trump presidency, the lingering radiation sickness of his court appointments is slowly poisoning us, a cancer in the marrow, repealing personal rights and unleashing police and corporate power. Just as the latest variant of Covid is subsiding, one state after another has begun declaring a state of emergency over Monkeypox. The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has dropped the usual qualified scientific rhetoric and screamed like a ragged street preacher that we are all going to die if we don’t radically reinvent the infrastructure of industrial civilization immediately, but the industries that control our governments are addicted to wringing every last possible petrodollar out of the ground, even if it exterminates the species. If you also happen to have one or more personal crises to deal with in your own life—which, these days, who doesn’t—it’s all rather a lot to try to stay on top of.

Government and corporate propaganda tries to foist a sense of responsibility for these crises on individual citizens and consumers: we’re urged to get out and vote, although because of gerrymandering, our votes only matter in a handfuls of districts around the country, and the majority’s will is reliably thwarted by the electoral college, the Senate. Petrochemical industry PR urges us to re-use our grocery bags and reduce our “individual carbon footprints” (a concept they invented) while they cremate the Amazon and pump billions more tons of carbon into the atmosphere. But because most of us are not heads of state or billionaires or corporate lobbyists or CEOs of major industries, our options to respond to these crises are few, and feeble. There’s an enervating sense of cynicism and despondency about the possibility of any agency or change: writing your elected representative feels as effective as writing to Santa, and protest as potent a ritual as sacrificing a goat.

People react to powerlessness under stress in a variety of ways. They avoid; they deny; they self-anesthetize. Personally, sitting at my mother’s deathbed, I decided that unqualified sobriety was no longer a tenable policy for me. Some people go berserk; others go limp and hopeless, waiting numbly for it to be over. With their attention spans unshackled in quarantine, some people were roused by moral outrage to revolt against the police state; others succumbed to delusional conspiracy theories and revolted against constitutional democracy. Anxiety and depression are endemic among the young, who know their inheritance was squandered and their future forfeited before they were even born. They are of course all heavily medicated, but this only numbs the sufferer, because the causes of their suffering are real, systemic, and unlikely to change, since those problems are to some powerful interests’ benefit. (I’m trying to imagine how I would feel if I were a teenager listening to Congress affect moral outrage over the pernicious influence of Instragram while shrugging “thoughts and prayers” at yet another school shooting, or the Supreme Court ensuring the right of your football coach to pray on the fifty-yard line while gouging one tooth after another out of the EPA.) Mostly we just try to get through the goddamn days.

I read the book of Mark, the first of the gospels, out loud to my mother, though I don’t know whether she consciously heard me. Reading it, I wondered whether any Christians have ever read this book. In addition to Jesus’ highly impractical dictates RE love and forgiveness that are among his most-quoted and least-observed, there’s a lot of nakedly apocalyptic rhetoric claiming that some of those listening to him, ca. 1st century AD, will live to see the end of days. He sounds a lot like a cult leader—telling everyone to abandon their families, give away all their wealth and possessions and follow him, don’t worry about tomorrow, the end is nigh. I’m not going to reassure you that Things Have Always Been Bad, that people have been predicting the imminent end of the world since long before Jesus; we are at a moment of converging crises, some of them potentially lethal to the species. But, in a way, I almost prefer a life-or-death crisis to the death-in-life of corrupt, dysfunctional business-as-usual; I appreciate it when life drops the fake nice-guy act and reveals its true face, and you can finally put aside your free-floating dread for grim certitude.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised; the surprising part is how long things stayed, at least locally, relatively placid. I came of age during a long plateau in the Cold War, after the convulsions of the late 60s had subsided, a time when, despite the constant low-level terror of nuclear immolation, America seemed as stable and settled as the Appalachians. The peaceful transfer of power was a problem in banana republics and ancient Rome. The worst President anyone could imagine was Nixon—a liberal Democrat by today’s standards, who was driven out of office for the kinds of penny-ante crimes Donald Trump bragged about daily, and whose political allies deserted him when it became undeniable he’d obstructed justice. My grade-school friends and I were all vaccinated because our parents had all lost an aunt or uncle to polio, smallpox, or TB; the worst we could expect to catch was chicken pox or mumps. In Maryland, it sometimes snowed in October. I feel like some evanescent creature born in a warm tide pool who thought it was the universe.

That time—which, while it lasted, seemed like the natural order of the world, stolid and inevitable as the seasons—turns out to have been an anomalous idyll, a fluke as ephemeral as a spell of pleasant weather in April. Now even the seasons aren’t as reliable as they used to be. All of recorded human history has elapsed in a brief Indian summer between ice ages. Widespread public respect for science was an educational artifact of the Cold War that didn’t last more than a generation; that tense postwar stability, a brief, uneasy breather from the bloodbath of history. Rationality, democracy, tolerance and pluralism have never been the norm in human civilization; they are aberrations—precarious, essentially unnatural institutions that have to be constantly propped up and protected, re-sold to every new generation. Evidently someone forgot to tell the current one. Base humanity always wants to revert to magical thinking, tribal loyalties, and the brutal hierarchies of the apes. All that ever kept the chaos at bay was a fragile consensual fiction, as imaginary and indispensable as money, or marriage, or the lines painted on the highway. We got complacent and lazy and forgot it was ours to lose. A reprieve is all we ever have.

My own deathwatch is over now, as our collective one will be soon enough. That brief false calm is already ending; with the overturning of Roe vs. Wade, the eyewall of the hurricane has hit. What I can tell you, as your advance man reporting from the time ahead, is that even though you’ve always known this was coming, it still comes as a shock; it still feels unreal. Intellectually, you understood it was inevitable, imminent, and yet it still arrived sooner than you expected. At some childish level you never believed it would really happen. You can’t believe that the people who seemed so confidently, eternally in charge have just absconded, that you’ve been abandoned, that you’re really on your own. It’s a relief, in a way, to have the waiting over at last, even though the reality is worse than you’d imagined, because the time when you could’ve done things differently is irrevocably over: you did what you did and, worse, did not do what you didn’t do. But, in a sense, to be abandoned is also to be freed. Once all the grownups are gone, it forces you to realize that you’re the grownups now. You’re the ones in charge. And what happens next is up to you.

Please never stop writing. You are my only reliable "advance man reporting from the time ahead".

"Like" is perhaps the wrong word to describe how I feel about this essay, but it's what that little heart up there is called. Deep, bittersweet appreciation and relief? Also, showing up in your comments after pretty much every new piece to say, "thank you, yes, that," isn't a particularly helpful contribution to you or your community of readers, but, well, there it is. Finally, I offer my heartfelt sympathy over your mom's passing. I recently lost my beloved Dad, and the experience (after a long, dark silence, combined with yearslong layered grief about US- and world politics, COVID, climate, and other personal stuff) has brought me back to writing, and, strangely, made me feel freer...like I've grown up. I'm barely able to describe this feeling, which is why I've returned to writing. OK, that's all for now. I'll keep quiet for a while!