Open Sesame

The Berlin Wall, the Constitution, and the Latent Power of Language

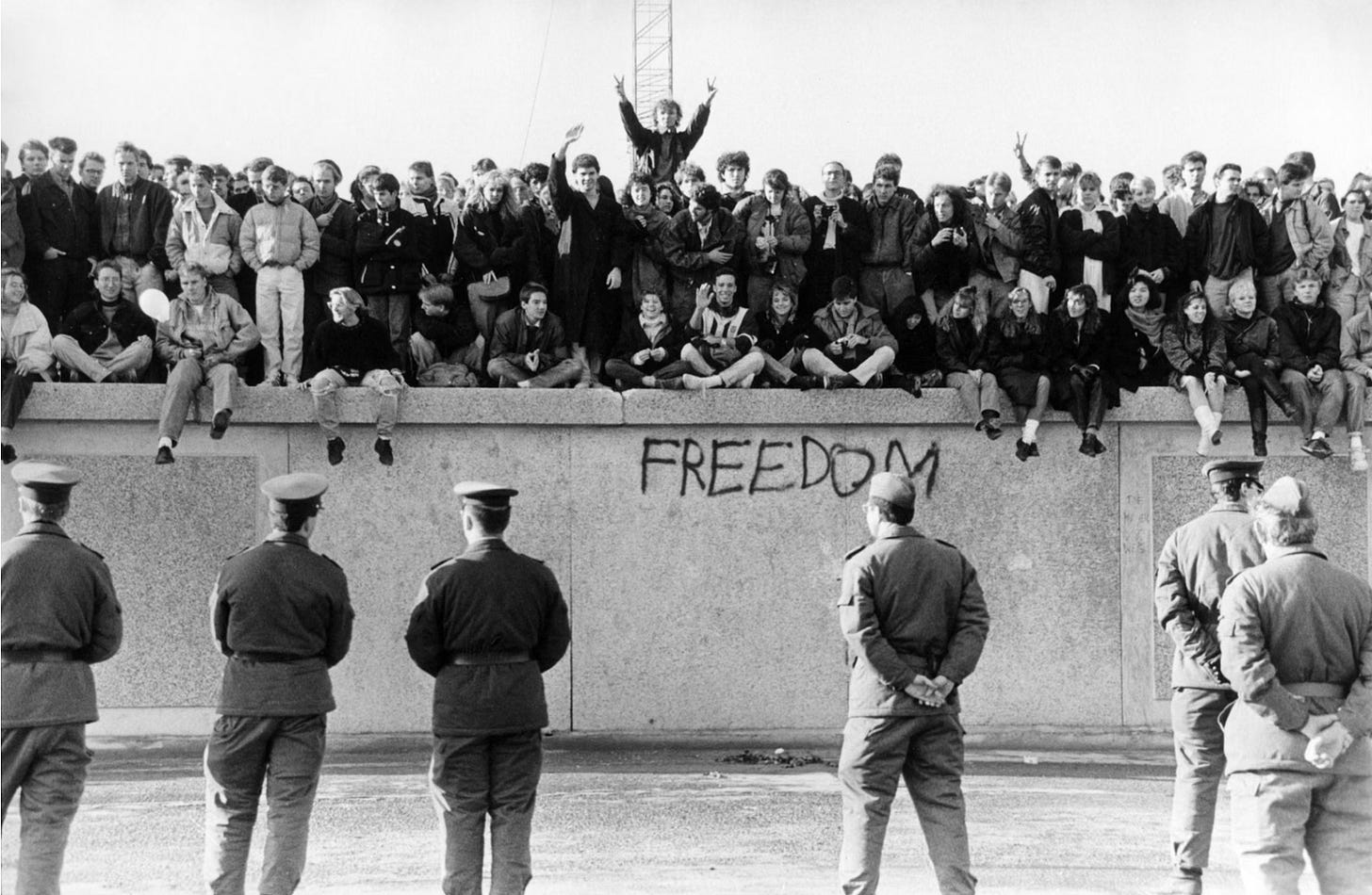

This last Saturday was the 35th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. At a moment when language feels silly and impotent in the face of dumb bludgeoning power, it’s heartening to recall that that wall—and, subsequently, the Eastern Communist bloc and the Soviet Union itself—was brought down by words.

On November 9th, 1989, an East German politburo member, Gunter Schabowski, made an announcement:

“…we have decided today, um, to implement a regulation that allows every citizen of the German Democratic Republic, um, to, um, leave the GDR through any of the border crossings.”

Communist governments routinely used to issue official statements that were universally understood to mean nothing—to have no relation to, or any practical implication in, reality. (There was a style of censorship-defying comedy in the late Soviet era wherein performers simply repeated official rhetoric verbatim and straightfaced. There was no need for a punchline; everyone was already in on the joke.) This particular statement was not wholly meaningless: the government was actually attempting to make some controlled, incremental concessions in response to mass protests that had recently unsettled East Germany, now known as the Monday demonstrations.

But a crucial difference between this and most East German government briefings was that, because of the recent unrest, it was attended by international journalists, who were more accustomed than their colleagues in state-sponsored media to asking aggressive follow-up questions. Schabowski was used to Communist bloc journalists, whose job was to transcribe whatever he said and then print it. So when journalists called out to ask him when this unprecedented policy would take effect, he seemed unprepared. Shuffling through the papers in front of him and glancing uncertainly up at his colleagues, Schabowski answered: “That comes into effect, according to my information, immediately, without delay.”

The assembled press immediately started leaving the briefing room to call their offices and file their reports on this world-historical scoop, at which point Schabowski, perhaps apprehending that he had ventured out of his depth, announced that it was now 7 PM, so regrettably the press conference would have to come to an end. But it was already too late: his announcement was the lead story on the East German news that night, and before long rather a lot of people had begun gathering at Berlin Wall checkpoints, waiting to be let through.

One Harald Jäger, commander of the Bornholmer Strasse border crossing, was eating a sandwich during Schabowski’s press briefing, and later said that he’d nearly choked on it when he heard the announcement. Earlier that day he had received instructions to arrest or shoot any trespassers, per standard policy. He called his superiors to check, Was this was for real? and was told No of course not. Except more and more people kept showing up.

There was a lot of confusion, indecision, and conflicting information throughout that night. At one point, border guards announced that all entries would be one-way only—that if you left, you couldn’t return. This was a hastily improvised stratagem to rid the nation of what the authorities were calling “provocateurs.” But by then a lot of students had already crossed over to West Berlin, whose parents protested in outrage, so eventually the guards conceded, okay well students are allowed back through. The crowds were like: Whaddaya mean, only students are allowed back? Finally the border guards, lacking any coherent guidance from above, caved. At 11 PM, Jäger, realizing that the situation was threatening to become dangerous for both the crowds and his guards, decided to open the gates under his control, without even checking IDs.

A lot of individual spur-of-the-moment decisions contributed to this cascade of events; Schabowski, when asked about the timeline, could have put off the question, said he’d have to check with his superiors and get back to them about that and hope everyone would just forget about it. Jäger could have stonewalled the crowd, or tried to disperse them. Everyone was conscious of the possibility of another Tiananmen Square; the Chinese regime had murdered its young en masse only five months before.

But the momentum of events was against them. And an instinctual genius that certain bureaucrats and border guards share with visionary (or just savvy self-preserving) statesmen lies in getting out in front of the inevitable, to ride history’s cresting wave rather than getting crushed by it. They channel the will of history like the planchette of a Ouija board. However the government may have intended the announcement, once enough people had taken it seriously, it was too late to do anything other than pretend they’d meant it. And only two years later the iron empire of the Soviet Union, with its massed tanks and arctic gulags, dread secret police and world-annihilating arsenal, had dissolved like cotton candy dropped in a puddle.

I love this story, because it dramatizes the contingency of events—how, despite the immense inertia, momentum, and collision of vast political, economic, and social forces, history can still pivot in an instant on a guy eating a sandwich. But I also think of it, more and more, as a model, or maybe just a metaphor, for the history of social progress in America. The cause of freedom and equality here has always advanced in much the same way as the wall crumbled, and for the same reason: because people insisted on taking bullshit seriously.

This analogy isn’t quite accurate. The East German government was trying to head off a revolution; they didn’t envision people dancing on top of the wall and taking sledgehammers to it and auctioning chunks of it off by the next morning. They simply lost control of events. The authors of the American Declaration of Independence and its Constitution were revolutionaries, who meant what they wrote, even if they knew they couldn’t implement those principles as policy in their own lifetimes, or even live by them themselves.

If you wanted to be cynical, you could call all our foundational documents bullshit—certainly all the people tacitly left out of that All men are created equal would’ve thought so. Some of the framers were slaveowners themselves who believed that slavery was natural and just; some were abolitionists who understood that slavery was a moral atrocity that violated the foundational principles of their new nation. But many of them were both: slaveowners who understood that it was an atrocity, because they were, like us, flawed and contradictory and hypocritical. They felt they couldn’t eliminate that institution given the economic and political realities of their time. Also, they needed the free labor. As is true of many writers, their words were better than they were.

But it’s hard to imagine that even the most idealistic, forward-thinking founders ever envisioned the enfranchisement of freed slaves, or of Native Americans, or Chinese immigrants, or their own wives and daughters—let alone that one day men would want to marry other men, or women other women, or that people would choose to change their genders. They, too, lost control of events. Whether by deliberate calculation, or as an artifact of its cobbled-together ideals and compromises, the authors of the Declaration and the Constitution had encoded fatal contradictions into those documents, a kind of virus or self-destruct sequence, that doomed the institutions of disenfranchisement and inequality to eventual collapse. In the same way that the formula E = mc2 made Hiroshima inevitable, the words All men are created equal foreordained not only Lexington & Concord but Fort Sumter, as well as Selma and Stonewall, Haymarket Square and Blair Mountain.

Empty rhetoric or not, hypocritical bullshit or not, people chose to believe those words, or to act as though they believed them; they took them seriously and ran with them. And soon enough the crowds came, massing fast at the gates, clamoring for entry. In every generation, a new wave of people demanded admittance, and those in positions of power were forced to make their own panicky, on-the-spot calls between resistance or compromise, crackdowns or acquiescence, slowly retreating by reluctant, grudging increments.

Dictators and demagogues regard language with careless disdain: words are just noises they have to make to get people to do what they want; they don’t actually mean anything. So they make things up for a moment’s convenience, contradicting whatever they said the day before, promising one thing to one audience and the opposite to another. They don’t take language seriously; to them, only guns and money are real. But some words are volatile, as packed with explosive potential energy as matter.

Linguists talk about “performative utterance,” in which to say a thing is to do that thing: I do. I resign. Open Sesame! You are free. The real power of those historic announcements and declarations came not from their authors, but from their hearers, who treated them not as aspirational but performative. Calling certain rights inalienable made them so—or perhaps revealed that they always had been. When enough people persist in taking bullshit seriously, it ceases to be bullshit, and becomes something else: a principle. A tenet. Eventually, perhaps, the law.

Such words are like incantations that manifest a new reality. A pro forma proclamation read aloud by an apparatchik accidentally brings down the wall that divides the world; promises made in oak gall ink on parchment have to be honored in blood on Maryland fields. Those highflown notions penned in calligraphy summoned not only the Minutemen, but revolutionaries of the future unimaginable to their authors, calling themselves Suffragettes and Freedom Riders, Black Panthers and Lesbian Avengers. It is a kind of magic; a lie that makes itself come true. Like those pulpy boys’ stories about rocketships and Martians that inspired generations of dreamers, crackpots, and daredevils, and ultimately left footprints on the Moon.

I love this. Didn’t know the history of how the East Germans bungled the announcement. It reminds me, in a way, of the weekend when Gavin Newsom, then mayor of San Francisco, announced that the city would be issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. That wasn’t enough to settle the question of marriage equality, there were still plenty of roadblocks and plot twists on the way, but it was a significant move forward. I was in San Francisco at the time, and it felt like the mayor’s announcement (performative language) had released an unstoppable outpouring of love.

“In every generation, a new wave of people demanded admittance, and those in positions of power were forced to make their panicky, on-the-spot calls between resistance or compromise, crackdowns or acquiescence, slowly retreating by grudging increments.”

…And so here we go again. Change is always spotty. Let’s pray no irreparable harm is done before these next four years can be over. Thanks for the perspective.