I always used to assume that the painter Giorgio de Chirico had died in the first world war, like gentle Franz Marc, because in any art history course I ever took or survey of modern art I read, I never saw anything he’d painted after 1920. But it turns out de Chirico lived long enough that he could’ve seen Saturday Night Fever in the theater if he’d wanted; he died in 1978. He just disappears from art history after 1919, when he renounced all his most famous and influential work—all the images you think of when someone says “de Chirico,” the ones you see on dorm room posters and album covers—in favor of a defiantly unfashionable, neo-baroque style. The Surrealists discovered his early work—those solitary towers and truncated monuments standing against green twilit skies, furls of smoke from distant locomotives at the horizon, tiny silhouetted figures rolling hoops through empty piazzas—around 1920, right after de Chirico had decided it was all crap. Later in life he became something of a crank—a flamboyant reactionary, staging “anti-Bienniales,” painting Roman gladiatorial scenes and self-portraits in Toreador costumes to mock accusations that he’d embraced Fascist æsthetics, and occasionally forging early works by himself (which he called verifalsi, or “true fakes“) to hoax the collectors and make a little extra cash. He became radically uncool, aprés-garde.

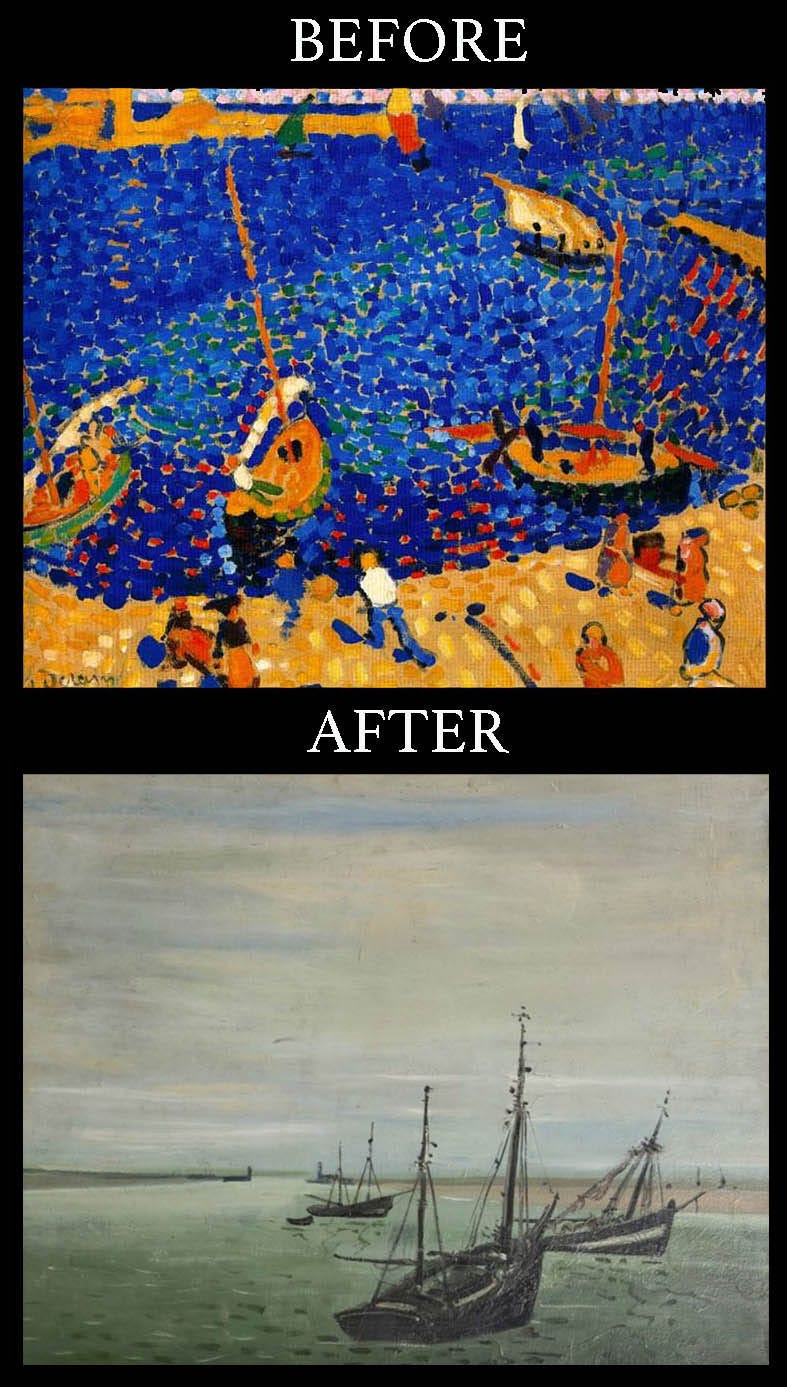

Same deal with André Derain, subject of a recent show at the Met alongside his more famous friend and colleague Henri Matisse. Together they were originators and core of the Fauves—a.k.a. “The Wild Beasts,” one of the cooler gang names of modern art movements (second perhaps only to Der Blaue Reiter, a.k.a. “The Blue Rider”). Rather than faithfully reproducing colors from life, they tried to transpose the relationships between colors and their emotional effect into their paintings—red tree trunks shadowed deep green and purple by their foliage, a face half-shaded in blue-green with one cheekbone daubed crimson, sunlight scintillating emerald and vermillion off a deep ultramarine harbor. Derain was to Matisse what Georges Braque was to Pablo Picasso: artists who started out doing much the same thing side by side, their work almost indistinguishable from one another’s, until, for some reason, their creative trajectories diverged: Braque was still doing vintage cubist paintings a la 1907 well into midcentury, while Picasso had become Picasso, chimerical giant of the twentieth century; Derain, on the other hand, ditched his brilliantly dappled palette for dull grays and browns, and his rippling sunlit scenes for still lifes so still they look like they’re carved out of granite. Even his late portraits look like statues, his Last Supper like a Monument to the Last Supper.

You don’t hear much about late de Chirico or Derain; you never see their mature work in art history texts or coffee table books. No one ever even calls it “mature,” because that would imply that their early work, the stuff critics esteem most highly, was preliminary, larval. After their revolutionary periods they become irrelevant, almost embarrassing, like a reproach to modernity, declining to conform to the dominant narrative of modern art. That narrative is one of progress, of constant innovation, one new school or movement eclipsing the preceding ones, each revolution overturning the last: impressionism, pointillism, fauvism, expressionism, cubism, futurism, etc. It’s a narrative that no longer describes the history of 21st century art, and we’re going to have to revise it unless we want to relegate our own era to a decadent coda, and our own creative lives to meaninglessness.

If you wanted to be perverse, or provocative, you might call artists like de Chirico and Derain the real revolutionaries—truly independent spirits who gave not a passing fuck about critical acclaim or popular opinion. They stepped disdainfully out of the mainstream to follow their own meandering paths into the wilderness without a glance back. The same artistic instincts, the same character traits that made these men such visionaries in their youths, and enabled them to make the creative breakthroughs they did, also drove their willingness to turn their backs on the revolutions they’d inspired: an invincible confidence in their own instincts over the world’s judgements. Just as Picasso and Matisse never stopped evolving—always experimenting, dropping new styles as soon as they caught on—they weren’t content to coast on past accomplishments. They ignored the critics and colleagues who preferred what they’d done in their youths as though they were audiences calling out for the top 40 hit they’d recorded decades ago; they flouted artistic and intellectual fashion to pursue their own private obsessions. Once their ways parted from critical and academic consensus, they disappeared from our view. But the world’s approbation was always incidental to their interests; if their work had ever met with public praise, it was only by accident.

I once spoke briefly to the novelist Robert Stone as I was getting a book signed at a reading, and told him I hoped he was working on something new. “It’s all I know,” he said, helplessly. In a way, I envy those artists who have no other options: they have One Thing that they do, and do that thing devotedly, compulsively, for a lifetime. Think of Charles Schulz hunched at his drawing board every day for fifty years, building a tiny, infinite universe we all now inhabit one gag at a time. Last month I saw that Philippe Petit, who once walked across a tightrope strung between the twin towers of the World Trade Center a thousand feet above the plaza one morning in 1974, was performing at the Church of St. John the Divine on the upper west side, walking through an installation of ribbons hanging in its nave twenty feet above the marble floor, at age seventy-four. It’s these obsessives who tend to become legends, who get called “genius,” because to become great at anything requires that kind of fanatical dedication, tens of thousands of hours of concentration and practice. The rest of us, somewhere between the adepts and the dilettantes, committed but not necessarily compelled, have to make more conscious choices.

Those of my own artistic cohort who’ve been ambitious and fortunate enough to make careers of their chosen art forms are now at a point in life when they’ve been doing the same thing for a few decades and become fairly accomplished at it, and a lot of them are beginning to get bored, antsy for a change. A longtime science reporter wrote a collection of personal essays; a pastor who wrote a one-act play is considering leaving the church to study dramaturgy; a great cartoonist put down his pen last year and has since put out three albums of original songs, while another graphic novelist is experimenting with three-dimensional comics, in origami and ceramics. I may not be the greatest writer of personal essays alive, but I’ve written some good paragraphs, lines I can look back on with satisfaction, and it’s time to decide whether to continue with this form and, if so, how. A novelist friend of mine, whose own policy is never to accept advances, and always submits her next book as a fait accompli, urges me to write whatever I want without consideration for what’s expected or likely to sell. This may be easy for her—she has a certain de Chirico/Derain quality herself, that same imperturbable certitude—but it’s harder for me to disentangle my own artistic interests from my sense of what the world wants, and is likely to reward me for. I was particularly interested in the central dialogue in the film American Fiction, between an older author who thinks a younger colleague is pandering to popular prejudice, while she—to whom the concept of “selling out” is about as meaningful as “original sin”—shrugs that she’s simply “giving the market what it wants.”

I know my novelist friend is right: for one thing, it’s pointless to try to predict what kind of work might resonate with readers, which is always a matter of inscrutable luck. More importantly, this kind of calculation is anathema to creativity. The artists I know who are among the most successful are also some of the most frustrated: they’ve been so well-rewarded for doing what they do that their agents, editors, and publishers don’t want them to do anything else. Don’t get all moody and philosophical on us now; people love your Instagram affirmations! Nobody wants to read about Amelia Earhart; how about another memoir? One writer friend’s grandmother once gave her some shrewd career advice. “What you should do,” she said, sucking on a cigarette, “is find out what kind of books make the most money. Then,” she concluded, with a triumphant plume of smoke, like one handing over a million-dollar idea, “write that kind of book.”

I can’t exactly admire either de Chirico or Derain; there was some correlation between their contrarian artistic impulses and reactionary politics. They each accommodated themselves to fascist governments in their respective countries: de Chirico painted an official portrait of Mussolini’s daughter and appealed to Il Duce to become director of an Italian art academy that would restore traditional values, and Derain was received as an honored guest in Berlin while the Nazis were occupying France—both of which everyone agreed, in retrospect, looked kinda bad. (Some critics have argued that de Chirico’s later paintings were burlesques of fascist ideals, their gladiators and wrestlers flaccid and sagging, and Derain’s defenders claim he was more a useful dupe than an active collaborator. But not everyone’s buying it.) I also don’t find their late work as interesting or as beautiful as their early inspirations; de Chirico’s neoclassical paintings never recapture the disquieting power of his eerie dreamscapes, and Derain’s late still lifes and portraits just look inert, muddy and dull to me compared to the shimmering glades and harbors of his Fauvist era. But who’s to say?—it’s not as if contemporaneous critics have the last word on anything. History is littered with masterpieces nobody liked at the time, from Melville’s to Mahler’s. Maybe a hundred years from now the consensus will be that everything after Cézanne was bullshit, and de Chirico and Derain will be counted among the very few artists who kept their heads through the hysterical crazes and hideous fads of the 20th century. Probably not, though.

What I can’t help but admire about them is their indifference to critics and admirers alike, their untouchable self-assurance in their own idiosyncratic instincts and judgment. I admire their doggedly following their own paths, even if I’m not as interested in where they led. I admire their cussedness. It’s a value-neutral quality in itself, cussedness, amoral and inæsthetic, and not one you can really emulate, anyway—it would be like trying to imitate originality. But such artists’ careers demonstrate that it is at least possible to move through this world unswerved by its capricious granting or withholding of approval. They’re examples, good or bad, to their fellow artists as we all feel our blind, groping way forward—or, sometimes, back—through the dark of creation.

Very few artists can survive seeing their work contextualized on a grand scale while they're still alive. The best thing you can do might be to just write a lot of stuff.

This is true of one of my faves : George Grosz. The circumstances surrounding his Berlin period were extreme but he was happy to teach art in New York after fleeing from Hitler.