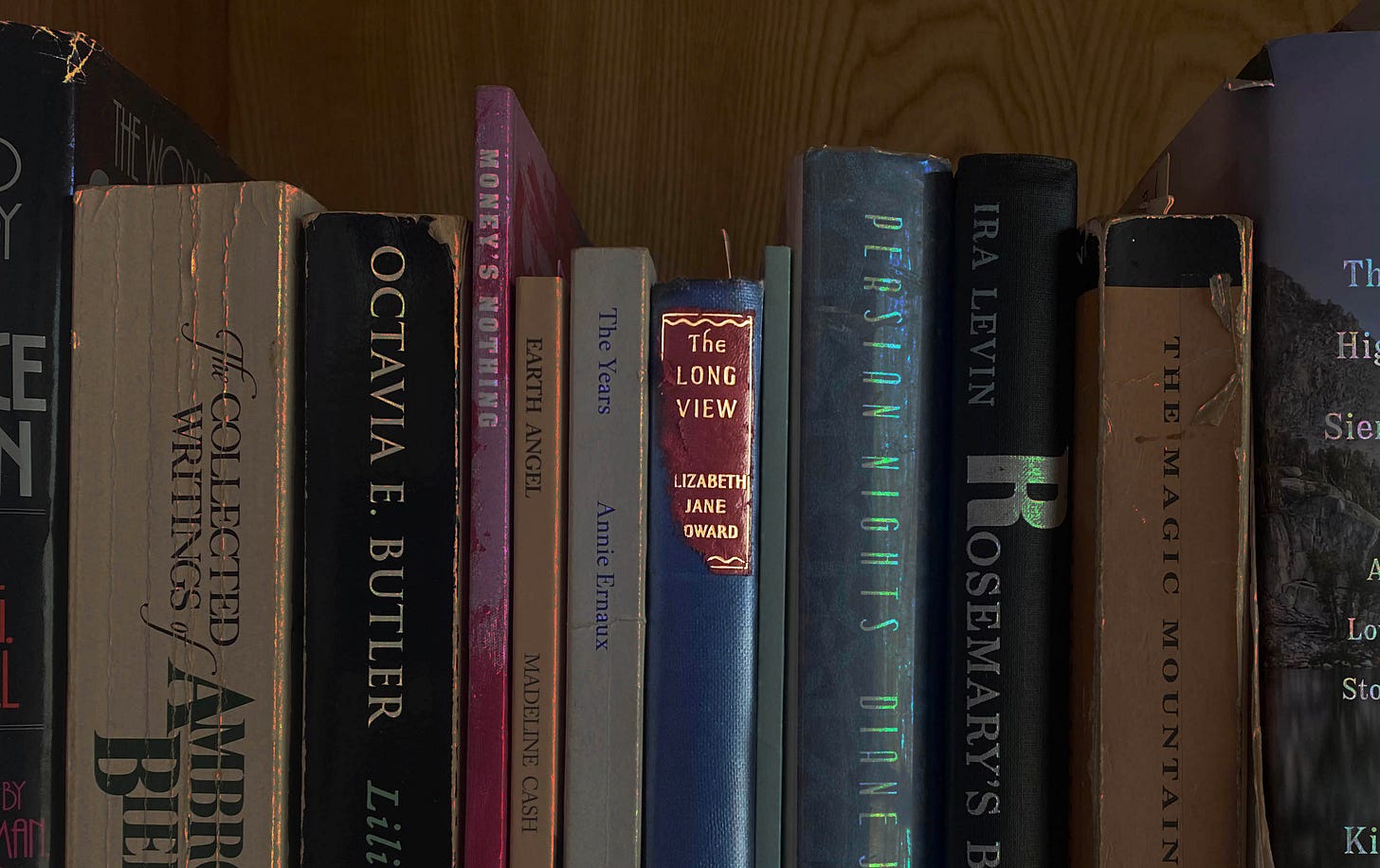

I stopped in at Bökin books in Reykjavik—the kind of messy, rambling used bookstore that seems like it probably has a cat in it somewhere, though so far as I could tell there was no cat. I was poking around in the narrow, cluttered aisle that comprised the English-language section—books crammed sideways into the shelves, books piled atop each other—where, for no particular reason, I pulled the least prepossessing-looking volume there from the shelf: a small blue hardback, its dust jacket long lost, the title, The Long View, stamped on the spine in faded gilt. The first line was: "This, then, was the situation." The opening paragraph is about a woman planning her son’s engagement party, every detail of which she can already imagine with tedious precision; the evening holds zero potential for interest or surprise. The obvious question is: so what will happen? I read the rest of the first page with increasing interest, almost perplexity; the prose wasn’t at all ornate or show-offish, but elegant and precise, with a quiet assurance, intelligence, and insight evident in every line. It reminded me of the reportorial opening paragraph of John Williams’s Stoner—the polished, unostentatious work of a master. I wondered: Have I just not read anything in English in a while, or is this really good?

It is really good. One critic wrote of this book: "Why The Long View isn't recognized as one of the great novels of the 20th century I will never know." (Nice to know I can recognize quality when I come across it uncurated, as when I finally find a shirt I like in a store but it turns out to cost $200. I’m reminded of the time I wrote an article to bring some overdue attention to a forgotten cartoonist, not realizing Charles Johnson had later won the National Book award for his novel Middle Passage.) It was written by Elizabeth Jane Howard, a midcentury English novelist best known for her multigenerational saga The Cazalet Chronicles, but she wrote more than a dozen other novels, co-authored a book of ghost stories, We Are for the Dark, with Robert Aikman (her contributions, like “Three Miles Up,” are very creepy and atmospheric), and is even credited with a screenplay (for Getting it Right, a more-interesting-than-usual 80s romcom). She was also, incidentally, married to novelist Kingsley Amis, and stepmother to Martin. Hilary Mantel wrote an eloquent appreciation of Howard when she died in 2014, arguing that she was a first-rate novelist, critically neglected because she was a woman and her chosen subjects—marriage and domestic life—are typically “feminine” preoccupations.

The Long View is the history of a marriage, told in increments a decade or so apart. The woman anticipating the engagement party is Antonia Fleming, whose own marriage is disintegrating, and whose children are both embarking on differently doomed marriages of their own. Near the end of Part One, we read: “The desire to go backwards, to retire into the life she knew, was very strong.” And then the book does go backward: each succeeding section takes place before the preceding section—a device I haven't seen outside of Charles Baxter's first novel, First Light, one of my favorite books. The conceit may sound gimmicky, but in the hands of writers like Howard or Baxter it seems as natural a way to tell a story as more conventional chronology: instead of What Happens Next, we learn How Things Got This Way. Baxter’s epigraph to First Light is from Kierkegaard: “Life can only be understood backward, but it must be lived forward.” Or, as Antonia thinks to herself: “I could manage the whole situation now, if only I could start at the beginning; what is difficult is the end of a situation that I began so badly.”

The book that The Long View first reminded me of was Revolutionary Road, another merciless vivisection of a marriage—but Richard Yates has always seemed bitter to me, as though he believes his characters deserve the sterile wasteland they’ve made of their lives, whereas even if Howard depicts characters who are callous or cruel, I never sense that the author is—though neither is she as forgiving as, say, George Eliot. She sees people clearly and unsentimentally, which I suppose, to readers who’ve spent their lives steeped in sentimental literature, reads like cynicism. The Long View shows how the enforced dependence of marriage deforms the personalities of both men and women and relations between them. Its protagonist, Antonia, is an intelligent, perceptive, capable woman who’s been passed from the care (and control) of one man to another her whole life: from father to seducer to husband to lover and back to her husband again, who finally discards her. At the story’s end—the book’s beginning—she finds herself, in her early forties, at the terrifying brink of being alone for the first time in her life. Her children seem condemned—determined—to make the same mistakes she did, or, at best, exciting new ones. On first reading, Antonia seems curiously detached from her children, resigned and unloving; it’s only after finishing the book that we understand what’s crushed the capacity for affection out of her, forced her into what Howard calls “crustacean self-containment.” Re-reading Part I after having finished the book, we see her as possessed of an impotent wisdom borne of hard experience, halfheartedly wanting to impart advice to the young that she already knows they won’t take, but realizing “she must perforce revert to claptrap.”

Antonia’s husband, Conrad, is of the same genus as the patriarch of Edward St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose novels, who casually inflicts the trauma that becomes that tetralogy’s trajectory: a man complacent of his intellectual superiority to everyone around him and his total control over every situation he encounters, whose boredom drives him to be cruel for his own amusement. A good villain makes for easy drama, so you might assume that these men are caricatures; and yet there is such a distinctive similarity to their pathologies that it makes me wonder whether it wasn’t a real syndrome conditioned by their time and place. “Young female readers today may view [Conrad] with incredulity,” Hilary Mantel writes. “They should not. He is faithfully recorded. He is the voice of the day before yesterday, and also the voice of the ages past.” The unchallenged authority and entitlement that the upper-class white men of the great colonial empires (America’s included) enjoyed—and the crushing pressure from outside and within them to appear to be something that no one could possibly be—deformed their psyches, made monsters of them. (I’ve never forgotten Frederick Douglass describing how even his naturally kindhearted masters became cruel in the roles imposed on them by slavery.) It also stunted and impoverished them. The middle section of the book, in which Conrad loses control of an affair, his wife, and his own emotions, is as sympathetic as he ever becomes, but by the end of the chronology he’s concluded that his only error was in letting his wife get too close, know him too well; he’s since sealed off all potential vulnerabilities and become absolute monarch of the empty hell of his self.

Does this all sound like a period piece now, the institutions and mores it describes obsolete? When Frederic Raphael was adapting Arthur Schnitzler’s fin-de-siecle novella Dream Story for Stanley Kubrick, he asked the director whether a lot of things hadn’t changed since 1900, especially relations between men and women. “Think so?” Kubrick said. I suppose marriage has changed in the seventy years since The Long View was published—just not, I suspect, as much as we like to think. The Long View is set in and around London between 1926 and 1951, an era when marriage was ostensibly undertaken for love instead of money, property, or inheritance (although, then as now, people seldom married outside their class), and divorce wasn’t yet a live option—meaning that people wed for less pragmatic reasons but still couldn’t renege on the deal, so that you likely married someone you barely knew in your teens or twenties and then had to get through the next half-century with them somehow. Marriage is even more of a mess now than it was then: its original utilitarian purposes now largely obsolete, this vestigial institution has, in the absence of the church, dependable careers, stable communities, or extended family, become the single flimsy pillar atop which people pile their entire identities, as well as the purpose and meaning of their lives. The proliferation of unconventional relationship structures—open marriages, throuples, polycules—suggests that a lot of people are wondering: what is this thing, marriage, anyway? Why are we all still doing it? A recent New Yorker article profiled a philosopher, Agnes Callard, who takes her own domestic life as text, asking what marriage is supposed to be; what is it for? It’s odd, in retrospect, that philosophers haven’t taken something so central to human life and society as a subject fit for serious philosophical scrutiny or interrogation—but novelists, those philosophers of the specific, have, with penetrating and dispassionate insight.

The general consensus on goodreads.com about The Long View (four out of five stars) is: good, but kind of a bummer. The characters are “unlikeable,” in “unrelatable” situations, with so much that’s “problematic” throughout. There seem to be a lot of readers who never graduated from YA, and a lot of adults who never developed beyond the worldview of adolescence. Esther Perel, in The State of Affairs, describes Americans’ peculiar attitudes toward infidelity: simple, moralizing narratives of transgressor and victim, trauma and pathology, an affair always a symptom. There are a lot of such facile, absolutist interpretations in The Long View: as a teenager, Antonia thinks she understands her parents’ marriage—a cheating wife and a duped husband who needs to know the truth; years later, a young soldier who’s housed with Antonia thinks he understands her marriage—a brutal husband and a captive wife who needs to be rescued. But Howard is far too smart a writer for any simple moralistic narratives; none of these marriages is what they seem. The Long View is testament to the fact that “traditional marriage” was never what a lot of people imagine it to have been—neither as virtuous as evangelicals pretend, nor as monolithic as the polyamorous suppose. It’s always been a very complicated contract, drawn up over decades by two complicit (which is not to say equal) parties, between whom the balance of power was always shifting, with a lot of subclauses, loopholes, and very fine print. These contracts are very different from formal wedding vows or prenuptial agreements, seldom written or even even spoken aloud; they’re more like treaties negotiated on the battlefield, under threat of betrayal, abandonment, and destitution.

My girlfriend and I just read (I for the second time, after an interval of many years) Herman Melville’s novella Benito Cerino, one of the most blood-chilling and unforgettable things any American ever wrote about race. I can’t tell you much about Benito Cerino in case you haven’t read it, for fear of breaking its sinister spell. It reads with the amorphous, slow-mounting dread of a horror story, and it’s structured not unlike Robert Louis Stevenson’s novella The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (which we tend to forget was originally written as a mystery): the protagonist observes a series of increasingly strange and disturbing events, about which he develops private suspicions and theories, until a climactic revelation exposes the truth, followed by an extended coda in the form of a document that retroactively explains everything we’ve witnessed. (It’s not unlike the denouement of a whodunit, in which the Inspector elucidates the clues and his deductions.) In both cases, Cerino and Jekyll, the explanation is obvious in retrospect, but it remains invisible to the protagonist because it lies so utterly beyond his capacity to imagine; it’s outside his conceptual framework. The mystery of Jekyll and Hyde turns on Victorian assumptions about class and virtue; Benito Cerino’s on antebellum assumptions about race and slavery. (Barely antebellum—though it’s set at the end of the 18th century, the story was written six years before the Civil War, and it’s suffused with the tension of that imminent violence.) It’s an extended test of the protagonist’s perception versus his prejudice, and of our own.

The Long View is less obviously structured as a mystery/solution, but its reverse chronology serves a similar purpose; we’re initially blinded by our own biases and assumptions about men and women, love and marriage, projecting facile narratives onto a far more complicated relationship that we only come to understand by delving into its past. One of the last lines of The Long View is: “This isn’t the end: it may very well be the beginning.” Having reached the end of the book (the beginning of the story) and gotten to the bottom of characters’ psyches and their entangled histories—or as near to them as we can get—I immediately went back and re-read the early chapters in light of what I now knew. We are shown everything from the start, but we can only see it in retrospect. The text of all history and literature is there for us to read, crammed into dusty bookshelves and forgotten, but we can’t see its obvious truths, obscured as they are by our received wisdom, our simple morality tales and ideologies. Life must be lived forward, but it can only be understood backward.

As someone about to celebrate 41 years of marriage let me testify to the benefits and strength that can be had from a long term relationship. The fact that it is very hard to navigate such a thing aside; if you are fortunate enough to find someone who complements your strengths and balances your weaknesses, and who shares an ability to commit to the idea of commitment, there are as many ways to navigate the relationships as there are couples willing to try. The benefits defy imagination, and the fullness of life shared with a worthy partner (married or not) include emotional growth, sharing of oneself and all that life puts in your path, and ultimately the growth of your ability to love.

You sold me! I just ordered the novel.