I’ve already written a lot about David Lynch, so I don’t think I need to add to it with a hasty appreciation on the occasion of his death. I’ll just write this personal note:

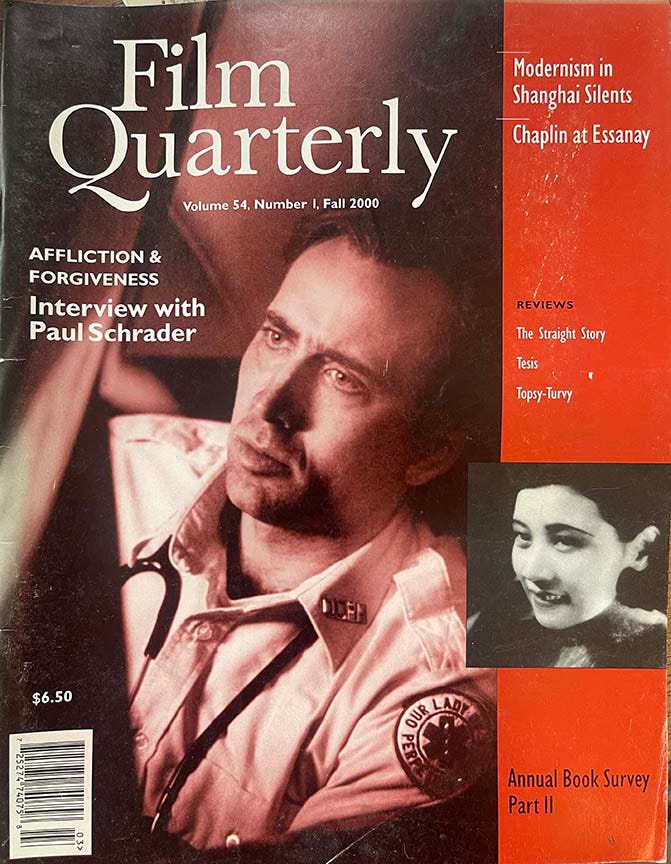

The first place I was ever nationally published was in Film Quarterly, then under the editorship of Ann Martin, and the second essay I wrote for them, in their Fall 2000 issue, was about The Straight Story. Eighteen years later, I wrote about what was to be Lynch’s last film, Twin Peaks: The Return. From that essay:

The real dreamer who’s woven the world of Twin Peaks is, of course, David Lynch. Lynch is over seventy now, and The Return is the late work—quite possibly the last work—of an artist looking back over his life and career, full of allusions to his forty years of filmmaking, and a meditation on age and death—his curtain call. Teasers for the series featured a lot of new, attractive young actors, none of whom proved to be major characters in the show. (In Episode 1 we meet a couple of twenty-somethings who at first seem as if they might be our new protagonists, a pair of young sleuths like Jeffrey and Sandy in Blue Velvet; the second time we see them they’re mauled into offal.) Most of its principals are in their fifties at the youngest; actors Catherine Coulson (Margaret Lanterman) Miguel Ferrer (Albert Rosenfeld) and Warren Frost (Doc Hayward) were all gravely ill as the series was being filmed. This isn’t a show, as Twin Peaks often was, about the melodramas of adolescence; it’s about the tragedies of senescence: people reckoning with their pasts, divesting themselves of illusions—“digging themselves out of the shit,” as Dr. Jacobi says—and facing the imminence of death. Harry Truman is fighting a terminal illness; amoral Ben Horne is trying to reform before it’s too late; Ed and Norma belatedly consummate their adolescent passion; Margaret Lanterman, the Log Lady, spiritual voice of Twin Peaks, dies. We leave Special Agent Dale Cooper on the verge of an unfaceable truth about himself. The tone of The Return is far darker than that of Twin Peaks, and only grows darker as the series approaches its end: it’s filled with long POV shots of driving at night, headlights barely illuminating the road ahead, and the final episode is one long nocturnal journey into the unknown. It all ends not with the girl saved and the natural order restored but with a scream of terror that plunges the world into darkness. The revelation of its last moments feels like a betrayal—an unraveling of the tale Lynch has spent decades spinning, and the unmasking of his most beloved hero. It’s like Prospero breaking his staff, an artist done with tricks and shadowplay, freeing his insubstantial creatures and abandoning his enchanted land to return, at last, to the real world. To go home.

I remember well the experience of watching the series, and those moments of thinking “what did I just see? And that was on TV?”

I'm going to miss him. The world will be less weird without him.