NOTE: This series of posts will be called “Antidotes,” because art, per Schopenhauer, is the antidote to life, and also in honor of the occasion that started my partner and me off on our joint reading series: we were having a zoom date for which, unbeknownst to me, she had prepared by taking an edible, which proved, as all edibles do 100% of the time, to be exponentially more potent and disorienting than she had expected, and she finally had to abandon all pretense of coolness and confess she was freaking out and and lie face-down on the bed while I tried to assuage her freakout by reading aloud to her from the only book on the shelf we agreed she could deal with, The Odyssey. This first entry in “Antidotes” is about Shakespeare, Elaine May, and threesome porn.

A lot of the humor in Shakespeare has always seemed cruel to me in an unfunny way I’m not sure Shakespeare intends; I don’t know whether humor has become more genteel over the centuries, per the thesis of The Great Cat Massacre, or if I’m missing some textual nuance or historical context (I wasn’t an English major), but instead of laughing along with the tavern wags and pranksters I always end up feeling sorry for the character who’s mocked and tormented, falsely imprisoned or publicly mortified, even if he is a prig or a hypocrite.

What struck me in Midsummer Night’s Dream, which my partner and I read as a literary palate-cleanser between two weightier works, was the perversity, even sadism (or masochism), of its enchantments. In the play’s supernatural subplot, Oberon, king of the Faeries, is peeved at his queen, Titania, because she’s abducted a human boy he covets (a backstory I’m gonna leave to grad students in Queer Theory to explicate), and so vindictively sentences her, his wife, to fall in love with someone grotesque and humiliating: “wake when some vile thing is near,” he croons. The vile thing turns out to be a boorish working-class guy and conceited amateur actor who also temporarily has the head of an ass, named, er, Bottom. Titania spends a bathetic night of lovemaking with Bottom, the sublime in bed with the ridiculous. In the morning, when Oberon releases her from her enchantment, she’s of course aghast, and he, satisfied with his vengeance and feeling tenderly disposed toward her again, forgives her. (She also, more improbably, seems to forgive him, or maybe she never realizes it was his doing—I myself would hold more of a grudge if my partner had tricked into a fucking a ham actor with a donkey’s head.) What it reminded me of, more than anything, was the porn subgenre of “cuckolding” (Shakespeare is very preoccupied with cuckolds—all those jokes about “wearing the horns” that confused me as a kid), in which some pallid, nerdy husband or boyfriend sits watching in ecstatic humiliation as his wife or girlfriend is vigorously debauched by a “bull” (instead of a donkey)—some big dumb beefy fuck-machine (who’s often also black—an icky racist subtext I’m gonna leave to doctoral candidates in Critical Theory/Ethnic Studies). A ritual of sexual debasement and betrayal for some sort of agonizing/ecstatic catharsis and reconciliation. Whatever floats yer boat, Oberon.

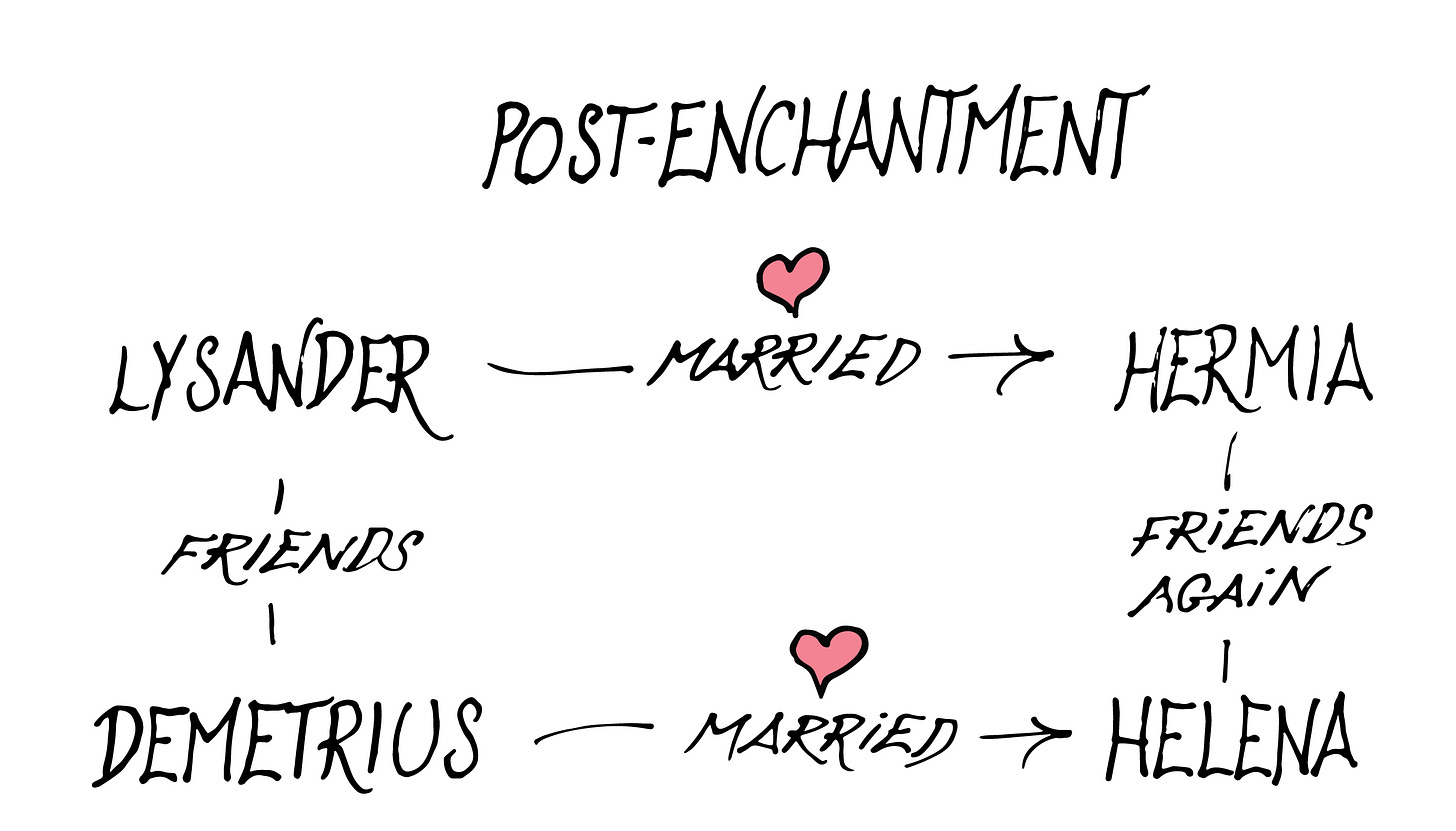

I am not always thinking of porn, but I couldn’t help but think of it again with regard to the play’s main plot, about four boring young people in an unhappy love quadrilateral. Lysander and Demetrius (male) are both in love with Hermia (female); Hermia is formally engaged to Demetrius, with her father (an asshole)’s approval, but she’s in love with Lysander; meanwhile, her best friend Helena (also female) is piteously in love with Demetrius, who has never once been anything but a dick to her.

Oberon overhears these last two squabbling in the woods, and decides he will gratuitously fuck with them by casting a spell on Demetrius to make him instantly fall insanely in love with Helena, who’s been following him around clinging to his pant leg while he says mean things to her. But, due to a humorous mixup, Oberon’s impish lackey Puck drugs/enchants the wrong guy, so that instead Lysander—who was, until now, planning to elope with Hermia—instantly falls insanely in love with Helena instead. Puck, whupped upside the head by his master, corrects his mistake, so now both guys are in love with Helena, to whom everyone’s been cruel for so long that, like a geeky girl suddenly invited to sit at the cheerleading squad’s table, she assumes everyone’s making fun of her.

Under the influence of this spell, Lysander doesn’t just fall in love with Helena, he also instantly falls insanely out of love with Hermia—not just cold or indifferent to her but nastily spurning her, literally telling her he hates her (also instantly forgiven as soon as the spell is broken). It’s all so complicated, abrupt and capricious it reminds me of the subgenre of wife-sharing or partner-swapping, whose standard plotline, such as it is, goes: I love you, but wait, what’s this?, all of a sudden I love this person instead, love her wildly as you watch with delighted horror, but no, ha ha, that was just a crazy little interlude, it’s you I really love of course, here I am back with you, now we are happier than ever, The End. Fantasies are just amateur, freeform fiction—fiction without craft, without an internal censor or editor, the adult equivalent of kids playing out illicit tableaux with Barbies and Kens (or, in Oberon’s case, Barbie and Eeyore). The wish-fulfillment that’s sublimated into high art in A Midsummer Night’s Dream is just more nakedly presented in lesser works such as “Busty amateur tinder girl had a amateur threesome” or “Panty Drawer scene 5.”

Everybody in Midsummer Night’s Dream, you may have noticed, falls in love instantaneously and insanely—they’re all just abruptly bonkers with adoration, loudly renouncing their old loves like middle-school kids disgusted by last week’s crush, and eager to endure any humiliation or abasement for their new ones. Shakespeare likes dramatic devices that allow his characters to abandon convention and inhibitions: magic spells, idylls in the forest, or holidays like Twelfth Night (the old Saturnalia), when everyone swaps social roles, sexes, and loyalties—masters change places with servants, women dress up as men, lovers renounce their beloveds and take up with their beloveds’ best friends instead. I realize they’re all under enchantment—it is a fantasy, after all—but the same thing happens in Twelfth Night (our previous Shakespearean interlude, of which we just saw a fun Afrofuturist production by the Classical Theatre of Harlem), in which no magic is involved. Romeo and Juliet, of course, same deal: blinding, ecstatic love at first sight, each ready to die for the other after a few days’ acquaintance (though this is at least plausible in their case, since they’re teenagers). I assume Shakespeare favors this device partly because he’s only got five acts, so if his characters are gonna fall in love they’d better do it fast so he’ll have time to introduce some hilarious (or tragic) complications. Kind of like “The Naked Time” episode of Star Trek, in which the crew contracts an alien disease that makes them all drunk as an excuse for accelerated character development. In Midsummer Night’s Dream it allows him to put his characters through every possible permutation—lovers, rivals, friends, enemies, spouses—in just a few scenes, like the high-speed orgy in A Clockwork Orange.

But I think he also likes showing our romantic passions as arbitrary, capricious and absurdly exaggerated because it represents us truly: Puck’s speaking for the playwright when he says, “those things do best please me/ That befall preposterously.” Romantic love—or rather Infatuation, which is what people usually mean when they say “love”—is preposterous: an ephemeral enchantment, a form of temporary insanity, when people act with clear-eyed certitude and absolute confidence out of infantile fixations they aren’t aware of and chemical impulses they can’t control. The French call it amour fou—crazy love. It’s a standard trope in rom-coms and love songs, but it’s not just a fictional device; I’ve experienced it a few times in real life. It was the most “in love” I’d ever felt up ’til then, the way people seem to feel in love stories and torch songs—Damascene, narcotic, zero-gravity love. I can still remember how it felt, and even remember the qualities that made me feel that way about those women, but as for the feelings themselves: evaporated. Not a trace. I have more direct access to my childhood enthusiasm for Ultraman or Tang than to my once-Byronic love for Cassandra Jameson. Whereas the women who were my girlfriends, flawed and overfamiliar to me, about whom I always felt ambivalent, conflicted and uncertain—in short, the ones I actually loved—remain among my closest friends as much as thirty years later.

Around the same time we read Midsummer Night’s Dream my partner and I also watched The Heartbreak Kid, as part of an Elaine May retrospective we’ve been curating for ourselves, which made for an accidental double feature about amour fou, erotic fantasy, and the fickleness of desire. Charles Grodin plays Lenny, a man who falls in love on his honeymoon—not, needless to say, with his bride. May’s film can be excruciating to watch; made in 1972, it anticipates what’s now called “cringe comedy” by a couple of decades—you get to watch Lenny frantically invent flimsy alibis for staying out all night while his wife is in bed with a sunburn, and break her heart in a seafood restaurant. Reading contemporaneous reviews of the film, a surprising number of critics seem to unreflectively identify and sympathize with Lenny, seeing him as a man oppressed by conformity, though to my eyes, at least, he seems delusional, craven, duplicitous and cruel, and so completely full of shit he even believes himself. (Attempting to flatter his girlfriend’s Midwestern family, he lauds the “honesty” of their dinner: “There’s no deceit in the cauliflower!”) My partner pointed out that his new wife isn’t objectively obnoxious, although he reacts to her as though she is; she eats with gusto (though she’s oblivious to food on her face—something Elaine May evidently finds embarrassing/endearing/hilarious, since it also happens in A New Leaf), sings irrepressibly (if loudly, and off-key), and wants reassurance that her husband is enjoying their newlywed sex. Jeannie Berlin (Elaine May’s daughter) doesn’t play her as a boor or a fool. She could just as easily be seen as uninhibited, fun, down-to-earth. But Lenny isn’t ready for down-to-earth; he wants an angel. Which he finds (as men in the cinema of the Seventies so often do) in Cybill Shepherd, who plays a funny, flirty college girl on spring break with her parents. (She acts, come to think of it, less like a real person than like the female lead in a screwball comedy, which we buy at face value because it’s a movie, but her arch dialogue and cool demeanor seem artificial in contrast to Lenny’s wife, who just acts like a person. It’s an act—the way a Midwestern college girl thinks a witty, urbane woman would talk.) After one or two brief exchanges consisting entirely of ironic banter, Lenny falls insanely in love with her, in a way that’s really only possible when you’re either under a Shakespearean enchantment or frantically escaping from something else.

A friend of mine likes to pose a question to people who are in the throes of such romantic/sexual obsessions: “If you weren’t thinking about this all the time,” she asks, “What would you have to think about instead?” Some critics see Lenny as a self-hating Jew, embarrassed by his unabashedly Jewish wife, who covets a golden-idol shiksa and all the respectable Midwestern Christian money she comes from. Which makes sense (May grew up in the Yiddish theater), although I, a clueless goy, was oblivious to this reading. I see Lenny as freaking out at the commitment he’s made, panicking at the permanence of marriage and the forfeiting of formerly limitless possibilities. It’s as if, having gotten married, he’s set foot on the unstoppable conveyor belt of life: next step, children; after that, death, with maybe a retirement watch or bowling trophy somewhere in there. You expend all this mental energy in finding and and choosing a mate, wooing and winning them, and then, once you actually have them, when it’s all been decided—then what? I still remember sitting on a rock in Central Park’s Sheep Meadow with my evil friend Ben twenty years ago, both of us, improbably, in happy relationships at the same time, asking each other what we were going to do with the 94% of our mental energies that had previously been devoted to ogling, scheming to seduce, or attempting to disentangle ourselves from various women. Once your long-sought goal is finally achieved, and all your frantic energies and designs and consumate bullshit are bereft of an object, life can suddenly look like a frightening blank.

Which is pretty much where we leave Lenny in The Heartbreak Kid. The film ends very similarly to The Graduate, made by May’s old comedy partner, Mike Nichols: with an awkwardly prolonged coda after the protagonist has won his dream girl, when most movies would’ve ended with an implicit happily ever after. At his second wedding reception (which looks a lot less fun than his first—instead of the Hora, there’s a lot of business talk, including the line, “There’s a lot of money in tear gas”), Lenny keeps repeating the same line of glib bullshit to one indifferent guest after another, like a candidate still reciting his stump speech at his inauguration (“So many people are concerned with taking things out of the country, you know, rather than making a contribution, and putting things back in,”)—until finally he’s reduced to using it on a couple of bored kids, who politely excuse themselves. He’s left saying, almost to himself, “I was ten”—on the surface, just a reductio ad absurdum of inane smalltalk, a clueless grownup’s attempt to find common ground with a child, but it’s also a half-glimmer of self-awareness, a reflection on the kid Lenny once was, and on what he grew up to be.

Lord, what fools these mortals be. We all want contradictory things—security and excitement, reliability and novelty, familiarity and difference. What we really want is rules, with exceptions—a speed limit you can break when you’re late, a job you love with a lot of vacation time, fidelity with the occasional fling. (It’s the formula for satisfying art as well: a theme with variations.) Everyone in Midsummer Night’s Dream gets a little holiday from real life, from society, even from love, but by the end of the play, as in partner-swapping videos, the status quo is restored and everyone’s paired up with a socially appropriate partner again—it’s not like Titania runs off with Bottom, having realized that this, at last, is the ass-headed man she’s always dreamed of. Although some of those pairings have been slightly reshuffled by the whims of love and magic. It only occurred to me belatedly that Demetrius is never released from his enchantment; he’s permanently left under a spell, in love with Helena forever (and apparently cured of his chronic dickishness). But then, his love for Hermia always seemed to be more about social status, his primacy as a suitor and rivalry with Lysander, than any real feeling. So his enchantment serves as a kind of correction, setting things right.

Still, though, you gotta wonder: does Demetrius still remember back when he loved Hermia? Does he know he’s not exactly acting out of free will? Does anyone ever? And does Helena care that her husband is only in love with her now ‘cause he’s under a spell? Would you? Lenny, in Heartbreak Kid, tries to do the same thing—to stay enchanted forever, to live in his fantasy. It’s like making the mistake of moving to the place you vacationed, only to realize, once you’re settled there, that the prices are high year-round and the winters are dull and the locals are never really gonna accept you. Lenny fell in love in sunny Miami Beach, but to marry his dream girl he has to move to wintry Minnesota.

The last we see of Lenny, he’s absently humming Burt Bacharach’s “Close to You,” a then-ubiquitous pop song played at both his wedding receptions—an ironic anthem for a story about fleeing in terror from the threat of intimacy. Come to think of it, both The Heartbreak Kid and A Midsummer Night’s Dream end at wedding receptions. Shakespeare’s play is weirdly structured: the plot is wrapped up by the end of Act IV, and all of Act V is an extended coda wherein the newly-married couples all lounge around at their wedding banquet watching a bad amateur performance of Pyramus and Thisbe (a tragedy about two doomed young lovers, one of the inspirations for Romeo And Juliet), commenting mockingly on it like the wisecracking robots in MST3K. While we, like them, sit watching the young lovers onstage, reciting their scripted lines, puppets going through the motions of the same old story of romantic confusion and disaster, marveling at their idiocy, not realizing it’s about us. Eventually the fantasy ends—the spell is broken, the video’s over—and you get to see your own reflection in the dark, just another doofus with their pants down.

A couple things to keep in mind — a comedy, performed live, is full of mugging and pratfalls and the unavoidable front-and-center consciousness that what you are seeing is a farce played out upon a stage. Films, especially films of a certain immersive-realistic bent, can feel more intimately-real than our own real lives. Othello loved not wisely but too well, leaving death and devastation in his wake, and leaving the audience devastated by how *everyone* loses. But A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a lark, a snowballing series of absurdities, and the play-within-the-play of the mechanicals is not a non-sequitur, it’s the point — it’s the meta-consciousness of the purpose of a play and what an audience does with it. The audience for Midsummer Night’s Dream is not sitting passively in comfy chairs absorbing the story. The audience is packed in with half the neighborhood, mostly on their feet the whole time and half drunk, or making crude jokes about who looks good in tights and whether what happened to Helena is just like what happened with Jane down the block last month! Context is everything — and context collapse being a blight particularly powerful in our age, I think we should push against it.

Shakespeare, over and over in the text, reminds us this play is nothing but a dream. Nothing more, nothing less. What happens in your dreams? Last night I had one in which I was some kind of cruel dictator punishing people for speaking out against my rule. That's about as far from my personality as possible, but...? Tortured 21st-century analyses like these miss Shakespeare's point completely. It seems modern comparative analysis is incapable of taking a text at face value. Sometime, as Freud said, a cigar is just a cigar.

Puck's final epilogue to the audience/reader:

"If we shadows have offended

Think but this, and all is mended -

That you have but slumbered here

While these visions did appear.

And this weak and idle theme

No more yielding but a DREAM."

Wake up, Tim.